The conquest of the New World is closely associated with the achievements of Spanish discoverers and conquistadores (conquerors). The other European nations, England, France and Holland will appear on the scene during the middle and later part of the 16th century. Portugal already had its share under the Treaty of Tordesillas, signed on September 5, 1494.

How then could Germans have contributed to the discoveries and carved their names among the conquistadors seeking fortune, and the Golden Man, “El Dorado”?

Toward the end of the 15th century, the obsession to discover a shorter, less costly passage to the South Seas and the Spice Islands, was at the forefront of western European maritime nations. For spices were almost as expensive as their weight in gold.

Unknown geography led many to believe that a sea route could be found on the western side of the ocean. It was thought that Christopher Columbus had located the passage that could bypass the Portuguese monopoly off the coast of West Africa, granted to them under the Treaty of Alcáçovas, on September 4,1479, that gave Portugal trade monopoly on the eastern coast of Africa.

Columbus had to overcome skepticism and hostility, such as at the Junta de Salamanca, when his proposal of opening a route to the Indies through a western passage, was scorned and ridiculed. The Admiral of the Ocean Sea persistence however, overcame doubt and antagonism and, on October 12, 1492, gave Spain its first glimpse of an Unknown World.

Land and gold were foremost on the European mind, but a shorter passage to the Mar del Sur, as the Pacific will later be known, was now within reach. The first sight of another world drove intrepid sailors and conquerors on an ocean they now knew, was not the end of the world.

It is the conjunction of two seemingly unrelated events that brought Germans to the shores of the Americas. The first was the conquest of the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlan by Hernan Cortez in 1519. That same year, Maximilian von Hapsburg, German King and Holy Roman Emperor died in Innsbruck.

Maximilian’s greatest territorial gains owed more to marriage than warfare. One of his sons ensured the Hapsburg’s hegemony over Hungary, while the other, Philip the Fair married Joanna, third child of Queen Isabella in 1496, ensuring thus a strong influence at the Court of Spain.

Joanna was not in good physical and mental health; she gave birth to several children, including two boys: Charles and Ferdinand. Queen Isabella knew that Joanna could not rule and inserted a clause in her will specifying that her daughter would be “Queen of Castile” with her husband Philip as her consort, but it will be their son Charles, who would wear the crown.

At the age of seventeen Charles became King of Spain, even though he had been born and raised in Flanders and knew little Spanish. Worst of all, a great cultural incompatibility prevailed between the Spanish and the Flemish. Few in Flanders and Spain could have foretold that Charles would emerge as a great European.

On a cold dawn of September 1517, Charles landed on a remote Spanish shore near the village of Asturias and met with the Primate of Spain, Cardinal Archbishop of Toledo. It was he who favored Charles as King and helped him present his claim to the various Spanish Courts, as was customary in Castile and other provinces. Charles had to swear to observe the laws and custom of each Court; he also took an oath that he “would not make further request for money” during the following three years, except for extreme necessity.

While in Catalonia, he was notified on January 11, 1519 that his grandfather Maximilian died. The title and crown of Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire was vacant.

Charles.I of Spain immediately set out to Germany to press his claim to the title. But to secure it required to “convince” the Electors through “incentives” necessary to forestall the ambitions of Henry.VIII of England and Francis.I of France. His treasury could not possibly answer his predicament and his oath to the Courts of Spain precluded him from requesting financial assistance.

Welser & Co.

Two powerful German merchant-banker families from Augsburg, the Fugger and the Welser (Fugger was a banker for Maximilian), were to lend the money to bribe the Electors, thereby obtaining noble lineage and power through bankrolling the nobility. Both families operated over many known world places, with offices and factories in Antwerp, Venice, Seville, Valencia, as well as in Germany and Austria. They were later joined by the banker Ulrich von Hutten, and other merchants and traders from the Hanseatic League.

The Welser fortunes were grounded in trade of goods and spices, while the Fugger were in banking and mining in Central Europe. The Welser bought Magellan’s last ship, loaded with spices, that circumnavigated the globe.

By 1530 their combined wealth was estimated to reach three million Rhine florins, or the equivalent of 16 tons of gold.

Anton Welser was at the helm of the Welser fortunes when he loaned 241,000 ducats to Charles.I in 1519. The Fuggers loaned 295,000 ducats. Both requested and received from Charles.I to pledge the entire Crown jewels and property of Castile when he became Charles.V, Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire.

Anton and Bartolomew Welser had already considerable experience in overseas trade and investment. Until the arrival of Hernan Cortes and his Aztec gold however, their main contact with the New World had been to procure the bark of a tree that grew in the West Indies, and was used as a decoction believed to treat syphilis.

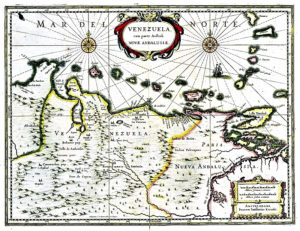

Anton WelserOn January 3,1528 the Welser signed at Burgos the contract, or Capitulación in Spanish, that granted them the governorship of a large and mostly unknown territory in the New World, today known as Venezuela. The contract was a guarantee of the King’s ability to repay the 241,000.00 ducats and an additional security of one million ducats of credit granted to the Crown. The Fugger banks were not involved in the Spanish arrangement.

The contract contained the same terms and conditions as those imposed upon Spaniards contracting for the rights of conquest. The terms were laid down by the Casa de Contrataciòn, founded in 1503 in Seville, where the Welser were prominent bankers and merchants.

They were permitted to conquer the lands; take the titles of Governor and Capitán-General (with perpetual annuities of 280 and 160 gold Castellanos, respectively); build fortifications from the King’s fifth, or twenty percent share of incomes produced by the territories; make slaves of the Indians (should they rebel); import horses and other domestic animals.

Since the time of Columbus, the island of Hispaniola had been the administrative center of the Antilles. In 1528, Bartholomeus V. Welser and Company settled in Santo Domingo and prepared their conquest of Venezuela. Ambrosius Ehinger was named its Capitán-General – Governor; he took on February 24, 1529.

From the start, the Germans had underestimated the fact that the New World conquest was understood to be the exclusive domain of Catholic Spain. The average Spaniard rose against the bankers from Augsburg and the Flemish lenders and merchants, that were elevated to Conquistadors, a status born from Spain, and from nowhere else. Worst still, these foreigners were more inclined toward Luther than Rome.

Ambrosius Ehinger

Located at the base of the Peninsula de Paraguanà on Venezuela’s north coast, the first established town was Santa Ana de Coro, built on July 26, 1527. As Neu-Augsburg, it was the first German colony in the Americas; the small peninsula was christened Kleine-Venedig or Little Venice. Ambrosius Ehinger was the first German Capitán-General confirmed by Seville. In the Spanish historical record, Ehinger is also called Dalfinger or Alfinger; his birth name Ehinger is used here throughout.

The settlement was watered by a small river; the coast covered with sparse, arid vegetation, dry forest and fiercely spined cacti, it was the least hospitable place to settle. The peninsula was almost empty of its original inhabitants, the Caquetio Indians, since many had been captured by Spanish slave traders, to work in the fields of Hispaniola; the others had fled South to remote hills.

Ehinger arrived at Coro on February 24, 1529, together with Philipp von Hutten, son of a Franconia prominent banker. It took Ambrosius five months to organize the governorship, and its first expedition to explore and map the land. He was convinced that the large body of water to its southwest, the Gulf of Venezuela, could be the route to the Mar del Sur, later called the South Sea, before settling on the Pacific.

The first expedition that left Coro took place at the beginning of April 1529. Ambrosius Ehinger set off southwest toward what is now known as Lake Maracaibo; he had explored the mouth of the lake during an earlier exploration of the coast.

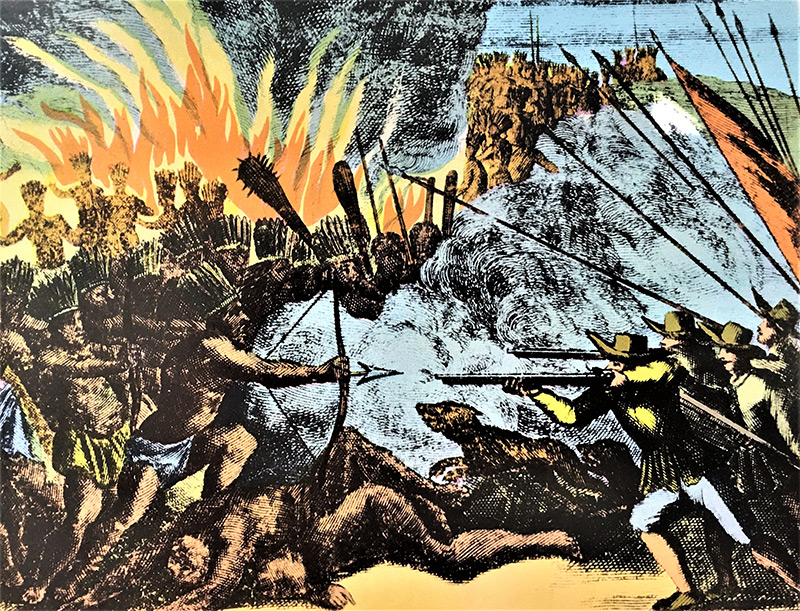

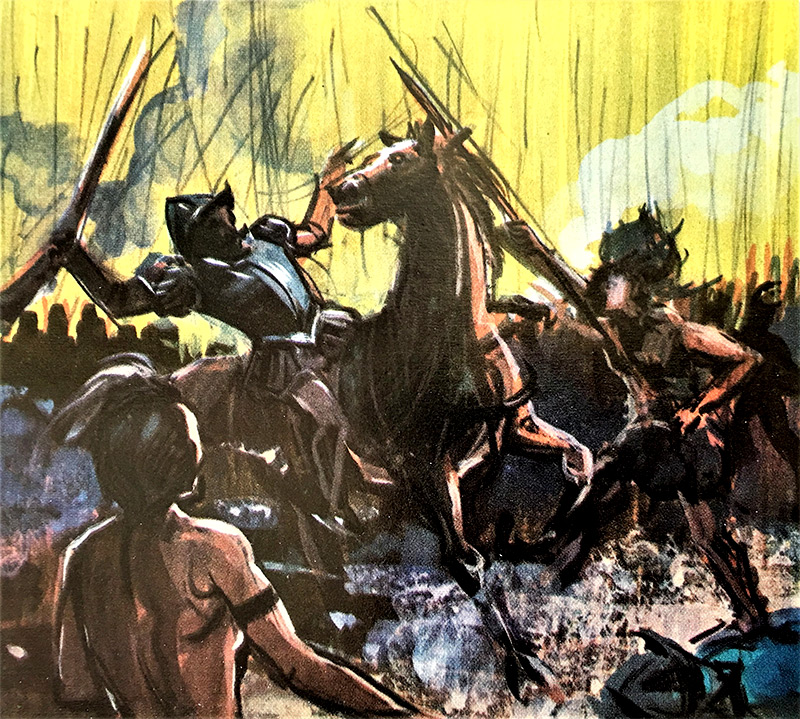

His army left Coro with 180 men, 37 horses, the Royal Notary and 150 Indians to carry supplies. The Royal Notary, by the laws of Burgos, had to read the Requerimientos (Requisitions), to the Indians. The Requisitions demanded that the local people should yield to the King and Christianity, or be liable to the steel of Toledo. The Requisitions were read aloud in Spanish, and did not care whether the Indians understood it or not, nor if there was anyone there to listen.

Away from the coastal plain, the first Indians with whom Ehinger clashed were the Jirajara, Cuibas and Coyones who did not know the sword or arquebus. Ambrosius together fought and parlayed his way through their territories and exchanged hawk’s bells, knives and other trinkets, for food, gold ornaments, and ornamental shells. The Jirajaras were not pacified until mid-17th century. He reached the indigenous town of Maracaibo on the lake shore, convinced that the large body of water would lead to the Mar del Sur.

The unknown territory, difficult topography and the number of hostile Indian tribes controlling ancestral areas, made their travel difficult, aggravated by the fact that feeding 180 men and 100 Indian carriers trekking 12-hours day required over a quarter of a ton of goods daily. This volume of food could not be found in the villages. The exploration that lasted 14 months took its toll, at the cost of 60 European lives, and half the number of Indian carriers.

This first expedition, after over a year of hard trek, with a mere 2400 Pesos in gold, returned to Coro on April 18, 1530. Almost all were half-dead, including Ehinger himself, hanging on to life only by the call of some golden siren voice. Meanwhile, the Welser house in Santo Domingo, having heard nothing from him for a year, presumed that he and his men had perished without a trace.

His long absence and with no news of his whereabouts, convinced the Welser that he had died and, in March 1530 named Johannes Seissenhofer as his temporary replacement; the Spaniards quickly called him “Juan the German”. With Seissenhofer was sent one Nicolaus Federmann. Seissenhofer died within weeks of reaching Coro from tropical disease, and Ehinger was restored to office. He named Nicolaus Federmann his lieutenant Governor, Captain-General and Coro’s Alcalde Mayor.

Before leaving he instructed Federmann to bring back the women and children from Maracaibo to Coro. But himself was not to stray farther than 30 leagues from the town. Ambrosius, fighting tropical disease, was then carried in delirium aboard a ship bound for Santo Domingo, to recover or die.

Nicolaus Federmann

Federmann, contrary to Ehinger’s instructions, promptly set out to conquer the land for the Welsers and find the route to the Mar del Sur. His argument for ignoring Ehinger’s command, was that Coro lacked resources to feed so many people and was full of idle men, ready for mischief. Nicolaus was a likeable man; most were ready to follow him to hell, which many had occasion to do on his great treks. He wrote Historia Indiana, the first ethnographic study on the Indians of the hinterlands of northwest Venezuela.

On September 12, 1530, together with 100 soldiers and as many Indian carriers, 16 horses and 2 monks, he struck out southwestward for his first expedition. He passed through the Caquetios territory, crossed the Sierra de San Luis through a 4500-foot pass, looking for a way to the South Sea. He entered the Jirajira territory in the Sierra de San Luis, and continued down the Tocuyo river in the heartland of the dwarves but valiant, Ayomán. They fought their way through this territory because the Indians did not understand the Requisitions.

Defeated, Ayománs joined the expedition, willingly or not, filling up for those other Indians that had died or escaped. The Ehinger “technique” to keep captured Indian carriers from escaping was to “rope them up”. Each carrier had a thick rope knotted around his neck attached to a main line, running the length of the column of carriers. Those unable to follow were beheaded on the spot without taking the rope off, not to slow down the column.

Heading southwest, they met a large number of Caquetios, who told them that the Mar del Sur was on the other side of the mountains to the South. The Caquetios were parents of those that had been hauled to work in Hispaniola and that took refuge away from the coast.

Warry of the foreigners, they agreed to send a number of men as carriers. But less than 5 miles from the village, they dropped their loads and escaped to the hills. Trinkets were exchanged which brought in 3000 gold pesos, or 5000 Rhine florins. The column kept going, crossing the Tocuyo river and reaching the land of the Gayón, where they learned that all men were each other’s enemies.

They then entered the land of the Acarigua, who resisted the invaders. They fought and burned their villages, leaving tens of Indians dead. Forty-six days of battle brought them to the water people, the Xaguas who lived on the Cojedes river. Further South they reached the vast plains of the llanos during the rainy season, where the land was under water, as far as the eye could see. It is difficult today to understand what drove these men through such brutal hardships and savage wilderness on a horrifying journey, now focused on gold, a more immediate and tangible goal than the discovery of a passage to the South Sea.

Traveling through the Guaiqueries territory, Federmann feared for their bravery. He entered the village with smiles and gestures of friendship. He had instructed his horsemen to calmly and slowly circle around the village. Once his soldiers were positioned, they launched their attack against the unarmed Indians that were confident in their ostensibly friendly visitors. The soldiers on horseback did the heavy killing, completed by the foot soldiers who, “slit their throats, like pigs”. This horrendous, and treacherous massacre left most of the 250 villagers dead.

Sickness and losses forced Federmann to turn back toward Coro on February 7, 1531. The return was more difficult than the southbound journey. They had to battle nature and the rains, the poison tipped arrows of the Indians and tropical disease. On March 17, 1531, exhausted and some dying, half of the expedition force staggered back into Coro, where Federmann met again Ambrosius Ehinger who had returned, in good health, from Santo Domingo.

Ambrosius was furious that Federmann overruled his instructions, and took upon himself to go on such expedition. He relieved him of his command and functions. Shaking with tropical fever, Federmann left Coro on December 9, 1531, for Santo Domingo, then onward to Augsburg, where he arrived at the end of August 1532.

Ehinger…Again

In spite of his and Federmann, harrowing experience, Micer Ambrosio as he was known in Spanish, was not to be deterred from his golden dream. So, at first light on June 9, 1531, together with 130 men and 40 horses, he headed West toward Lake Maracaibo. A hundred-plus Indians carried the supplies. They crossed the mouth of the lake and reached the settlement Ambrosio founded in 1529 on the indigenous village of the same name.

They then moved up the Socuy river and through difficult topography, brushing aside minor oppositions by local people, alternately hauling and hacking their way, crossing a succession of landscapes, headed South.

The invaders frequently fought brief but bloody battles, with the Chiri Indians, among others. The infantry was most effective with their long swords. It was on the plains of the Jerira river that Ambrosius received confirmation of what he had heard from the Maracaibo tribes who traded tropical produce, for gold ornaments, salt and painted cloth with people “somewhere” in the mountains to the South. Once more, was heard from various tribes he fought and parlayed with, what had been heard elsewhere, that “where salt comes from, comes gold”.

Heading South from where Cucuta now stands, they reached the high mesas above 8000 feet and the Pemeno tribe territory around the Tamalemeque trading center. Many battles later, Ehinger and his troop reached the Paramos de Chachira and suffered from cold, hunger and merciless assaults by natives on all sides. There was no relief from attacks; the Indians burned their houses, not leaving any food or standing shelter behind.

When Ehinger reached the Pacabueyes territory, and the Pauxoto village, he collected 24,000 gold Castellanos. His way to forcefully and rapidly collect gold was merciless. He corralled all the people in a tight stockade with no food or water. A few were then let loose to collect gold to pay for their brethren’s safe exit.

This brutal form of extortion was applied efficiently on other villages, such as at Tamara, a peaceful village were people worked copper, gold and silver. Many Indians died there because they either could not pay or were asked to always bring more. This expedition was recorded as the most inhuman and cruel in the history of this bloody conquest.

Iñigo de Vasconia’s Trek

and the 24,000 gold Castellanos

Before heading further South, Ehinger picked one of his lieutenant, Iñigo de Vasconia, 24 soldiers and Indian carriers to carry the 24,000 gold Castellanos back to Coro. Vasconia had three months to make the round trip and return to join Ehlinger’s column, with more men.

Long passed the allotted time, and worrying about gold and men, Ambrosio, selected Esteban Martin with twenty men to search for the missing party, and the gold. Martin reached Maracaibo with no major hurdle, but there were problems with the Onotos Indians in the vicinity. He went out to the Indian territory and after many skirmishes, fought ruthlessly in retaliation for the death of 14 Europeans lost in a previous battle. He received five arrows and wounded had no alternative but to stay in Maracaibo, while five of his men went to Coro to keep searching for Vasconia.

Vasconia’s party did not return the way they traveled South with the army, and got lost on the return trip through thick swamps. There was no food to be found; all men were exhausted and starving, some dying. Vasconia decided to bury the gold, and marked the location with signs on surrounding trees. In dire need of food, three men found a foraging Indian woman they killed, and ate. Indian carriers were not spared either, a number met the end of the woman, others escaped.

Esteban Martin returned to Coro and was cured of his wounds. He tried to re-trace Vasconia’s route, but could not find where the gold was buried. In a hamlet called Maracaibo (a name used in multiple locations), they found one of their own, Francisco Martin, almost naked with a bow and arrow. They took him back to Coro. He could not add anything to Vasconia’s tragedy nor did he remember where they buried the gold.

Years later rumors carried the story that when the group got lost, they split the load of gold among themselves. The Indian carriers by then were either dead or had fled. The group lost most of the gold when they tried to use badly made rafts on a river, some drowned with the gold strapped to their back. The remnants of the group were helped back to the Maracaibo settlement by Indians.

Martin, had an ankle and foot wounded during the fight with the Onotos, that were badly infected. While in Maracaibo he missed Vasconia by a few weeks, that was returning to Coro by another route, helped by local Indians.

Still hurting from his wounds, Esteban Martin returned to join Ehinger, together with 82 soldiers. The expedition was attacked time and again, and in a small valley where Martin tells of arrows coming from all sides. Ambrosius was struck in the throat by a curare tipped arrow. The arrow was removed; the wound sucked and human grease from a dead Indian applied to it; to no avail. The founder of Coro and Maracaibo died and was buried under the roots of a Ceiba tree. The valley was christened, Valle de Micer Ambrosio. The survivors retreated toward Coro which they reached on November 2, 1533; there were 35 survivors.

Virreinato de Santa Fe and Capitania de Venezuela

On July 19, 1534, by the Charter issued in Sevilla, Federmann should have been named Capitán-General de Venezuela y Cabo de la Vela, subject to his lieutenant being a Spaniard. The Charter was issued again on October 5, 1535, subject to confirmation from the Council of the Casa de Contrataciòn in Spain. At that time Jorge Espira, acting Capitan General would have had his commission expired.

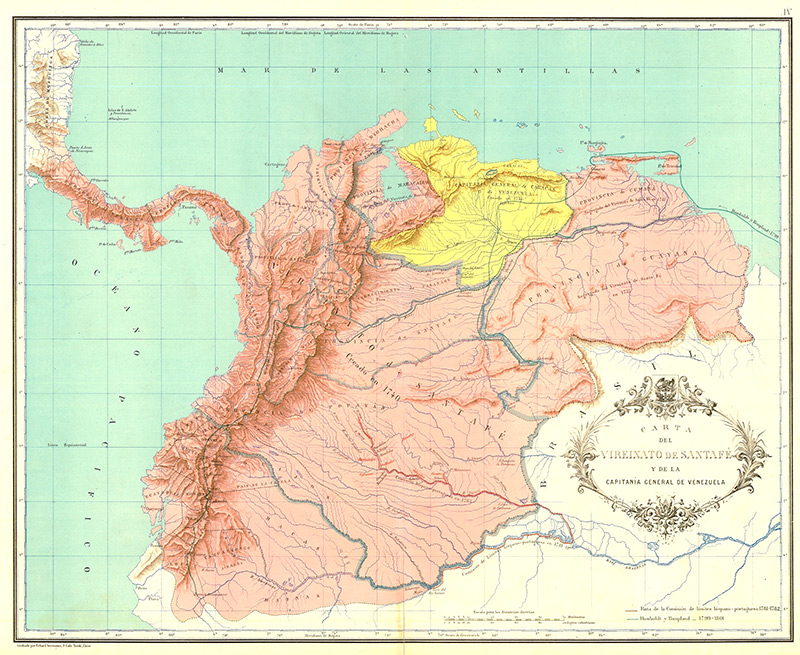

At the time, the land under conquest in South and Central America was roughly divided, for “administrative” purposes, between the Virreinato de Santa Fe (pink) and the Capitania de Venezuela (yellow) on the map. Frictions between Spanish groups however, were frequent and often violent since the land was still little explored. This state of affair created conflicts between the conquistadors because boundary lines between administrative authorities were then only in the process of being addressed. In the field therefore, no one knew for certain where one was.

Courtesy Wikipedia.com

The geographical area of the Virreinato de Santa Fe was extensive, covering the countries known today as: El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Costa Rica and Panama to the North. To the South: French Guayana, Suriname, Guyana, Colombia, Ecuador and northern Peru. The Capitania de Venezuela then covered mostly Venezuela, excluding, at that time, the Lake Maracaibo area.

Brazil was the dominion of Portugal, under the Treaty of Tordesillas, dated June 7, 1494, that divided the conquest of the New World with Spain; it was signed on July 2, 1494; Portugal ratified it on September 5, 1494.

Over the last preceding years, Fray Bartolomè de las Casas’ writings exposed the wrongs done to the indigenous people of the New World. The writings did wake up European people, the Crown and a powerful Church, for whom it was obvious that dead souls could not be converted.

The Spanish legal system started to address the problems of the new territories’ management, the encomienda system, and the brutality of settlers. Enforcement was next to impossible, in remote locations and communication gap. Moreover, the antagonism and perpetual rebellion of the Indian population, resulted in lack of economic performance of the new territories, that was no less of a major driver for change.

Undeterred by the cost of their American venture, the Welser were strengthened in their beliefs that El Dorado was within reach when the galleon Santa Maria del Campo docked in Seville on January 9, 1534. On board were millions of pesos in gold and silver bullions from Peru, the ransom of Atahualpa Inca, the 13th and last Inca.

What drove these men was chiefly the thirst for gold, driven by the legend heard which was heard time and again of El Dorado, the Golden Man. Over fame and rewards, for the individual, danger add the epic of life gave such enterprise, the impression of overcoming nature and one’s frailties in distant and unknown lands.

The major difference between German and Spanish conquistadors however, was short term tangible rewards for the business oriented Welser, that needed a reasonably fast return on their investment; while the Spanish Crown on the other hand, saw the New World as its exclusive domain, to be set in its own culture and Catholic religion. Rewards and fame of course were constant dreams for all concerned.

Georg Hohermuth is Jorge Espira

Georg Hohermuth from Speyer-am-Rhein, is also referred to as Georg von Speyer. In the Spanish record he is known as Jorge Espira the last name an adaptation of Speyer as Espira. He landed at Coro as the new acting Governor on February 6, 1535. As a young man he worked in the banking house of Anton and Bartholomeus Welser in Augsburg. He was the bank “confidential” agent that accompanied Ehinger to the new Capitania General de Venezuela. The Spanish last name Espira will be used throughout.

Espira met Nicolaus Federmann in Coro. The later, aware of Ambrosius Ehinger’s death, had agreed to return to the Capitania as the commander of the fleet from Europe, that carried Espira by way of Santo Domingo. The best Federmann got was the title of Governor, subject to the Lieutenant Governor be a Spaniard and receipt of the signed Charter, that Pedro de San Martin claimed he did not receive. Meanwhile, Espira was the acting governor.

Espira recognized he had a need for such an experienced man, and promptly named Fecermann Captain-General. Nicolaus’ immediate task was to map the western boundaries of the lands controlled by the Welser, that included Cabo de la Vela. The land is arid with scarce resources, including water, hard on men and beasts alike.

Constant attacks by aggressive nomad Indian groups, the Motilones and the Guajiros among others was costly in lives. The result of this trek, beside the mapping of the land, were hardships and no tangible reward, read: no gold.

In May of 1535, Espira, with many veterans from previous expeditions, and seconded by Andreas Gundelfinger from Augsburg, launched his own exploration. On his team was a new comer, Philipp von Hutten, whose diary will be an important source of information. Espira had an impressive force of 409 soldiers, cross bowmen, pike men, arquebusiers, 60 horses and hundreds of Indian carriers. Crossing the mountains of Xidehara, he quickly clashed with the Guajibo tribe killing many and capturing about 80 men. The remaining Indians fled further South, joined by other groups, and mounted a damaging counter-attack on the Europeans.

Espira sent his vanguard to the South through the Sierra de San Luis, the old Federmann route. On June 26,1535 the bulk of the army attacked Acarigua the first village in the Vararida valley. They kept going and destroyed the next village Itibona, which they burned, and captured over 50 of their men.

Orejón a soldier who strayed from the group, was seized by the Indians; his sword was found in a hut. In the village ruins were also found Orejón’s remains, half eaten and burned. For the death of the Spaniard, Hutten diary tells us, Espira had Indians ripped to shreds by war dogs, witnessed by their brethren.

After a month in the vicinity of the village, they left the sick and wounded, under the command of Sancho de Murga and Andreas Gundelfinger. Espira’s instructions were to catch up with the main group as soon as the men could. The instructions were ignored; the sick and maimed headed back to Coro. Of the 180 men, only 40 soldiers and 9 horsemen reached the town, the others perished.

With 130 men, 30 horses and over 100 Indian carriers, Espira continued his march South. On February 5, 1536, the army arrived at a village on the banks of the Apuri river. Beyond the southernmost reaches of Federmann’s old trail, they entered the llanos, truly tierra incognita.

Like an ocean, its tall grass undulating under the winds, the llanos stretch southward for over 1000 miles to the upper reaches of the Amazon. A land flooded during the rainy season and a sweltering inferno in the dry season.

On March 19, 1536, 700 miles from Coro, Espira and his men reached the banks of the Rio Ariporo, a tributary of the great Rio Meta, where he met the Wakiri tribes from whom they learned that their goal was within reach, a few weeks South in the high sierras.

When they reached the territory of the aggressive Choques the rainy season had started. Between overflowing swamps and narrow canyons they were at a clear military disadvantage. Esteban Martin, Espira second in command, was attacked while looking for a way out. Captured with two other soldiers they were drowned by the Indians; many others European were wounded.

They kept following narrow valleys in the mountain range, crossed the Opia river into the land of the Guaipies. In a hamlet they found pieces of gold and silver which the Indians said came from beyond the mountains. Their efforts to breach the high valleys and steep rock faces of the lower Andes to find a pass failed. They were close, about 40 miles from Sogomosa, the eastern most village of the salt people, the Chichas of the Muisca federation and its great wealth in gold, emeralds and the legendary origin of their quest, El Dorado.

The many battles against men and nature over their 1500 miles journey from Coro, had taken their toll. They were among the Huitotos who fiercely defended their land. Upon reaching the Rio Magdalena in the heart of the rainy season, Espira decided to turn back. It will take close to a year for the bedraggled remnants of the expedition to return to Coro. Over 300 dead, not counting Indian carriers, for less than a handful of gold was the Governor’s reward when he entered Coro on May 27, 1538.

A few weeks later, mined by tropical fevers and wounds sustained on the long expedition forced him to resign from the Capitania-General. He left for Santo Domingo to file a formal complaint against Federmann with the Audiencia. His resignation was rejected, and he was asked to return to Coro and resume his duties. He died and was buried there a year later, on June 11, 1540.

“El Dorado” the Legend

The Muisca called themselves muexa from the chibcha language, meaning “people” or “humans”, a common definition by many ancient communities, throughout the world. The capital of the confederation, Bacatá, located in today’s modern province of Cundimarca, is rich in copper, salt, gold and emeralds. The main bohio or village, was on the site now called Bogotá.

El Dorado’s legend speaks of a cacique (chief) from Guatavita, who found out about his wife’s adultery. He banished and condemned her to be sexually abused by the wretches and derelicts of the village. In despair, with her baby girl in her arms, she threw herself in the Muisca sacred lake Guatavita. The husband, driven mad with remorse and guilt, answered the shamans’ call for redemption. Each year, on the day of banishment, he had to throw gold in the lake to pacify his wife and daughter souls, and the gods of the underworld.

Each year, on the fateful day the legend says, the chief had his body covered with gold dust. He would then board a raft, together with few select members of the priesthood. The party rowed the raft to the middle of the lake, and with prayers and incantations, threw gold artifacts in the lake as atonement to the gods of the underworld. The chief bathed in the water releasing the gold dust to the depths and the deities, while begging his wife and daughter for an impossible forgiveness.

The legend of the Golden Man spread far and wide. It was later “seen” post-conquest, from the depth of the Amazon to the remote coast of the Pacific, and in the mountains of the green and white Cordilleras. Some search for him still.

Philipp von Hutten

Young Philipp von Hutten belonged to a noble family from Franconia, and was raised at Charles.V Court. He worked in the Welser’s banking house in Germany and Sevilla, and landed at Coro, together with Ambrosius Ehinger, on February 24, 1529. He then served on Espira’s expedition as field officer, and returned at the head of a few men to Coro.

In 1539, Charles.V revoqued Federmann’s commission and returned Espira as Governor. Espira was in poor health after the strains of his expedition, due to tropical disease and wounds sustained during the expedition. At Espira’s death in June 1540, in December of that year, Hutten was named Governor of the Capitania de Venezuela.

Like his predecessors, the thirst for fame, riches and the Golden Man, drove him out of Coro, on August 1, 1541. His field officer was Bartholomeus Welser.IV (Jr). With about 180 men 50 foot-soldiers and over a hundred Indian carriers, followed Federmann’s trail to the llanos. They then crossed the Rio Bermejo and clashed with the fierce Omeguas. Hutten was severely wounded with an arrow in his ribs which he removed with the help from a mestizo curandero, or medicine man.

Later his route took him through Indian ancestral lands, among which were the Choques, a no less fierce tribe than the Omeguas. They came close to Ocuarica the land believed to be that of the mythic Amazons, that met men only once a year. The first months of 1545, unable to breach nature, Indian hostility, sickness and wounds, forced Hutten to return to Coro.

One of Bartholomeus Welser Jr. assistant, Pedro de Limpias, suggested they stop to rest in the new town of Tocuyo, where the temporary Governor, Juan de Carvajal resided at the time. Hutten unespected arrival sounded the end of Carvajal’s hopes of being ever named Capitán General-Governor. Hutten was aware of the persistent hostility between Germans and Spaniards, hostility even more acute in Tocuyo.

A violent verbal exchange underlines this conflict when Hutten told Carvajal that he had to “report to the Welser and His Majesty”, to which Carvajal screamed “there is nothing here for the Welser but for His Majesty!”. The following day Hutten had dinner with Carvajal and informed him of his plans to leave for Coro the following morning, he was assured of safe passage.

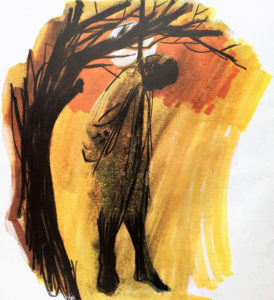

The following days in the hills over Coro, Hutten and his group settled for the night and went to sleep in their hammocks. They did not think that guards were necessary so close to the town. At dawn, Carvajal took them by surprise, unarmed, had the officers chained and their throats slit. Bartholomeus Welser Jr, was decapitated. Hutten asked to confess to Padre Fructos de Tutela but, history record that Carvajal screamed, “let him confess in hell!” and, with a machete, chopped his head off.

Juan de Carvajal

In late-1542 with the departure of Diego de Bastidas to Santo Domingo, Coro was mismanaged to such extent that Indian groups repeatedly attacked the town.

Revolving incompetent and greedy governors brought confusion, fear, crime and hunger to the community. Laws received from the Crown, the Audiencia, and the office of the Bishop of the Indies, aimed at improving the management of the new territories and better treatment of the indigenous people, were ignored.

Claims to Hispaniola and Spain moved the Audiencia in Santo Domingo to send Judge Juan de Frias to Coro to get a full report on the situation. Frias had to first, visit Margarita, Cubagua and the Paria Gulf and, given the urgency claimed by Coro, sent ahead Juan de Carval as provisional Alcalde Mayor.

Carvajal hate of the Germans, and Hutten in particular, was well known. At Hutten’s hearing as Captain General by the Audiencia in Santo Domingo, Carvajal wrote “it is not of service to Your Majesty that in this province there be a governor that is not a Spaniard”. He was overruled.

The call for fame and gold did not escape Carvajal. Frias had received written order from the Audiencia that did not allow him to stray from Coro, under any circumstances. Prior to Frias arrival, falsifying legal documents and in collusion with crooked officials, Carvajal forced the town people to move out and settled in Nuestra Señora de la Pura y Limpia Concepción del Tocuyo (Our Lady of the Pure and Immaculate Conception of Tocuyo), he founded in December 1545.

Everyone from the town, men, women, servants carrying babies and chickens moved out of Coro, willingly or not.

In early-1546, Judge Juan Perez de Tolosa arrived in Coro, a competent and careful man, to replace the incompetent Frias. His priority was to capture and sentence Carvajal for his numerous crimes, especially that of Hutten, named personally by Charles.V. He quickly moved to Quibor where he was informed his prey resided over the last few weeks. In the early morning, he seized him unguarded.

Carvajal confessed to his crimes one of which being the most heinous, the killing of unarmed men and high officials of the Crown. Judged and found guilty, Carvajal was sentenced to death by hanging. The sentence was executed the following week. Two years later, the King ordered that those associated with the deaths of the Germans be found and severely punished.

Within ten years of the death of Philipp von Hutten, Bartholomeus Welser Jr. and their companions, the contract with the Welser was terminated. There will no longer be German governors in the New World.

Federmann…Again

Upon his return from Germany, towards the end of 1536, Federmann planned his next expedition South, and knew then about jurisdictional claims between the Capitania of Venezuela and the Virreinato de Santa Fe, aka New Granada. The boundaries were not yet clearly defined, since most of the territories were still in the discovery stage. Claims of control and ownership raged between Coro in the Capitania de Venezuela, Santa Marta in the Virreinato de Santa Fe, the Real Audiencia in Santo Domingo, and the Casa de Contrataciòn in Sevilla.

Federmann never received ratification of his nomination as Capitán-General and Governor. The Casa did give the ratified Charter to the Welser, but they delayed its transmission while in the middle of negotiations with Federmann, who demanded rewards for his work, beyond acceptable terms. However, the Charter ultimately did reach Santo Domingo, and was forwarded to the Crown Commissioner Pedro de San Martin at Coro, who held it up pending resolution, in view of unacceptable terms related to the functions of the Spanish lieutenant Governor.

For his plan to reach the Muisca homeland and El Dorado, Federmann had large number of Indians captured to carry the army’s supplies and, with 200 men, 60 horses and hundreds of Indian carriers, headed the way he came back on his last expedition. For a year Federmann roamed the Carora region still heading South, with corresponding damages to the indigenous population.

His main concern however, one might call it obsession, was the governorship of the Capitania, so much so that he named his second in command, Diego Martinez to keep the army travel plans, to head toward the mountains, while he went back to Coro.

Diego Martinez, in February 1536, came in contact with a brigade of soldiers from Santa Marta. Jurisdiction again brought Spanish factions in conflict. Both groups looked at each other warily; the ones from Santa Marta standing for what they believed was their territorial rights, while those of Coro stood their ground to save their lives. To avoid an armed clash, Martinez was forced to find another route to the central mountain range.

Federmann re-joined the troops. They trekked hard through impossible terrain, battling Indians and jaguars alike. Hunger was the common enemy, so much so that a few men lost their sight. They had to kill horses to eat. Tropical sickness also killed a number of Europeans and Indians. At each hamlet they were told the now old story, that gold was on the other side of the mountain range.

In the highlands, they ultimately entered a beautiful valley Federmann called the Valle de la Alcazares. The lush green confined valley with numerous streams, was surrounded by grey granite peaks. In this pleasant place, he received the most unpleasant surprise, Gonzalo Jimenez de Quesada, from Santa Marta, had already set up camp there.

Birth of Another World

In 1536, the Europeans, unbeknown to each other, where heading toward the Muisca homeland in three separate armies, lured by the tales of El Dorado and fables of gold and emeralds; a land in the heart of the Virreinato de Santa Fe, that will later be known as Nueva Granada. By now, all knew this was not the route to the Mar del Sur.

From the Capitania de Venezuela, an army under Nicolaus Federmann had marched through 1000 miles of jungle, the llanos, and brutally cold mountains. The environment and Indians had decimated his army. When he arrived in the Muisca homeland, it numbered less than 200 weak, starved and emaciated men, on this third and last trek from Coro.

At the same time, an army led by Sebastian de Belalcazar, who had recently assisted Pizarro in the Conquest of Peru, was appointed Governor of Quito he founded, as well as the towns of Popayan and Cali. He had traveled 800 miles and arrived in late 1538 in the Muisca highlands, with 166 well-equipped men, in good health and spirit.

On April 6, 1536, Gonzalo Jimenez de Quesada, the lawyer turned conquistador from New Granada, headed South from Santa Marta 900 miles away on the Caribbean coast with 800 soldiers. He was the first to reach the land of the Chibchas in central Colombia, and read the Requerimientos (Requisitions), to the Zipa Tisquesusa, at Bacatá capital of the Muisca confederation. In 1537, he also found Lake Guatavita in the Codillera Oriental.

It was not Quesada’s idea to head South looking for gold, but that of the Governor of the Virreinato de Santa Fe in Santa Marta, Pedro Fernandez de Lugo. Two years before, Federmann had requested three supply ships loaded with food, men, horses and weapons from Santo Domingo, but one of the ships was blown off course in a hurricane, and landed at Santa Marta. That was how de Lugo was informed of Federmann’s plans of conquest by the captain of the ship’s loose mouth. De Lugo moved fast, for gold and country.

By the time Belalcazar and Federmann arrived, Quesada had already pillaged the riches of the Muisca towns. Gold and emeralds had fueled his soldier’s fanatical zeal. To avoid a feud that would have been fatal to all in the midst of numerous enemies they agreed to split the booty three ways, though not evenly, to later plead their respective claims to both jurisdiction and treasure, before the Spanish crown.

On April 27, 1539, Gonzalo Jimenez de Quesada, Nicolaus Federmann the last German conquistador, and Sebastian de Belalcazar joined together in a public ceremony and proclaimed the founding of Santa Fe de Bogotá, capital of New Granada and later, the capital of the Republic of Colombia.

Bibliography

Historia General y Natural de las Indias – Fernandez de Oviedo y Valdez, 1851

Old Panama and Castilla del Oro – Dr. C.L.G. Anderson, 1944

Historia de Venezuela – Epoca Prehispanica, Isaac J. Pardo, 1975

The Art of Prehispanic Colombia – Sam Enslow, 1990

Historia de Venezuela – Descrubimiento y Conquista, Isaac J. Pardo, 1975

The Spanish Conquest in America – Sir Arthur Helps (1813-1875), 1966

Colombia Before Columbus – Armand J. Labbè, 1986

Admiral of the Ocean Seas – Samuel Elliot Morison, 1970

very good submit, i actually love this website, carry on it